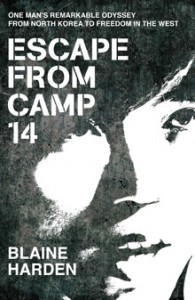

The heartwrenching New York Times bestseller about the only known person born inside a North Korean prison camp to have escaped. With a New Foreword.

North Korea’s political prison camps have existed twice as long as Stalin’s Soviet gulags and twelve times as long as the Nazi concentration camps. No one born and raised in these camps is known to have escaped. No one, that is, except Shin Dong-hyuk.

In Escape From Camp 14, Blaine Harden unlocks the secrets of the world’s most repressive totalitarian state through the story of Shin’s shocking imprisonment and his astounding getaway. Shin knew nothing of civilized existence—he saw his mother as a competitor for food, guards raised him to be a snitch, and he witnessed the execution of his mother and brother.

The late “Dear Leader” Kim Jong Il was recognized throughout the world, but his country remains sealed as his third son and chosen heir, Kim Jong Eun, consolidates power. Few foreigners are allowed in, and few North Koreans are able to leave. North Korea is hungry, bankrupt, and armed with nuclear weapons. It is also a human rights catastrophe. Between 150,000 and 200,000 people work as slaves in its political prison camps. These camps are clearly visible in satellite photographs, yet North Korea’s government denies they exist.

Harden’s harrowing narrative exposes this hidden dystopia, focusing on an extraordinary young man who came of age inside the highest security prison in the highest security state. Escape from Camp 14 offers an unequalled inside account of one of the world’s darkest nations. It is a tale of endurance and courage, survival and hope.

Published in 28 languages and selected by the Christian Science Monitor, the Financial Times, the South China Morning Post, Slate and Huffington Post Canada as a best book of 2012. School Library Journal named Escape as a 2012 best adult book for teens. Kobo, the ebook publisher for independent bookstores, named Escape to its list of top 50 books of 2012, and Itunes eBooks lists it among the 2012 top sellers in nonfiction. Indigo, Canada’s largest bookseller, picked Escape as the eighth best book published in 2012. The Readers Choice Awards of Goodreads, the online book club, selected Escape as the fifth best history/biography books published in 2012. A year-end rave review in Foreign Policy Journal described Escape as “one of the best books ever written on the indignity of life and death in North Korea’s vast labyrinth of political prisons.”

“In depicting the depravity of North Korean prison life, Harden’s book is an important portrait of man’s inhumanity to man… A remarkable and harrowing tale.” — The Washington Post

“A book without parallel, Escape from Camp 14 is a riveting nightmare that bears witness to the worst inhumanity, an unbearable tragedy magnified by the fact that the horror continues at this very moment without an end in sight.” — Christian Science Monitor

(In March 2015, three months after Shin Dong-hyuk told the author that he had lied about some details of his life in North Korea, this new foreword was added to all new printings of Escape from Camp 14.)

FOREWORD

SEOUL, SOUTH KOREA

Early in 2015, Shin Dong-hyuk changed his story. He told me by telephone that his life in the North Korean gulag differed from what he had been telling government leaders, human rights activists, and journalists like me. As his biographer, it was a stomach-wrenching revelation.

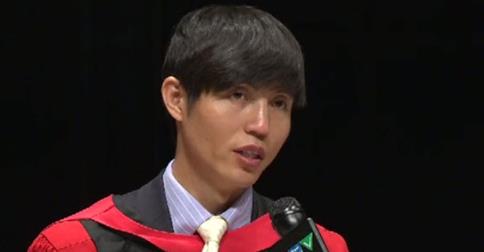

It was also news. In the nearly three years since Escape from Camp 14 was published, Shin had become the single most famous witness to North Korea’s cruelty to its own people. He posed for photographs with the American secretary of state, received human rights awards, and traveled the world to appear on television news programs like 60 Minutes. His story helped launch an unprecedented United Nations inquiry that accused North Korea’s leaders of crimes against humanity.

When I got off the phone with Shin, I contacted the Washington Post (for which I had first written about him) and released all I then knew about his revised story. Then I flew to Seoul, where Shin lives, to find out more. This foreword explains what I learned. In two weeks of conversations, Shin was less secretive and more talkative than he had ever been during long rounds of interviews with me dating back to 2008. He seemed relieved to be correcting a story he felt had become a kind of prison.

Shin told me that when he defected to South Korea in 2006, he made a panicky, shame-driven decision to conceal and reorder pivotal episodes of his life in the gulag. He hid his role in the execution of his mother and brother. He omitted a singularly painful session of torture that shattered his faith in himself. He did not mention that he lived most of his youth in a political prison that was not Camp 14. He told this version of his life to interrogators from South Korean intelligence and the U.S. Army. He then repeated the narrative for nearly nine years, rarely changing a single detail.

Shin told me he is now determined to tell the truth. Regrettably, he has told me this before. It seems prudent to expect more revisions.

Other survivors of the camps are angry at Shin, accusing him of undermining their truthfulness and weakening the international campaign to pressure North Korea to shut down the gulag.

In assessing Shin’s credibility and the changes in his story, it is important to know that he has multiple scars consistent with extreme torture. Trauma victims like him tend to struggle with the truth, especially in the linear narrative form that journalists, judges, and policy makers are best able to understand. The memories of trauma victims are often fragmented and out of sequence, and the stories they tell can be shields behind which they try to hide.

“The most genuine narratives of going through political violence are never completely coherent or finalized,” said Dr. Stevan M. Weine, a specialist on the impact of political violence and a professor of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He has treated trauma and studied trauma victims from Bosnia, Kosovo, Central Asia, and Africa. Between conversations with Shin in Seoul, I telephoned Weine and told him about Shin’s evolving story.

“When someone goes through profound trauma and I don’t hear a disjointed story, I am suspicious,” he told me. “Shin appears to have been exposed to prolonged and repeated torture. We can expect that this would have a major impact on every aspect of who he is, on his memory, his emotional regulation, his ability to relate to others, his willingness to trust, his sense of place in the world, and the way he gives his testimony.”

In Escape from Camp 14, I wrote that there was no way to fact-check many parts of Shin’s story because North Korea is largely closed to the outside world and it denies that political labor camps exist. But other gulag survivors had told me Shin knew things only an insider could know. Human rights investigators who had talked with scores of camp survivors found his testimony credible and precise. When this book appeared, Shin had already become a key primary source for major reports on the North Korean gulag.

Still, as I emphasized in the book, I worried about his capacity for truthfulness. I wrote that he had repeatedly lied to me. Two chapters in Escape from Camp 14 present him as an unreliable narrator of his own life.

In retrospect, I should have done more to examine the psychological dimensions of his relation to truth. It would have prepared me for what Shin disclosed in 2015, more than six years after we met and started working on the manuscript.

Shin’s altered story

The story Shin now tells is considerably more complex—and in some ways more disturbing—than the one he told upon his arrival in South Korea in 2006. In the new version, he escaped twice to China, not once. He lived in two bordering political prison camps, Camp 14 and Camp 18.

In his revised story, Shin said he was born in Camp 14, a “total control zone,” but when he was six or seven the border of that camp shifted. His home village, he said, was then incorporated into Camp 18, the slightly less brutal prison next door. North Korean government records seem to support his new version but do not conclusively prove it, as I will explain below. In any case, all the available evidence suggests that he was born and raised in a political prison.

In Escape from Camp 14, Shin said that when he was a small boy in the camp, he lived among children and adults who were destined to be worked to death as slaves without any possibility of release. As such, they were not allowed to see photographs of Great Leader Kim Il Sung or Dear Leader Kim Jong Il. But when his village became part of Camp 18, Shin said his status improved marginally. The food was no better; indeed, he said there was less of it. Another Camp 18 survivor confirms this irony, saying that because Camp 14 had better farms, it always had slightly more food.

In Camp 18, Shin did see photos of the Kims. He was also issued, for the first time, the uniform of a North Korean school pupil. While public executions for attempted escape were common in Camp 18, Shin said that as he grew up, prisoners were paid with food coupons for their work and, over time, some were released and allowed to become ordinary residents of North Korea.

These revisions in his story, while significant, do not alter the evidence of torture on Shin’s body. Indeed, he now says he was tortured more extensively by prison guards than he had previously been willing to admit.

In addition to being burned over a fire and hung by shackles from his ankles, which he had earlier described, he said guards used pliers to rip out his fingernails. Scars on his hands and the partial amputation of one finger support the claim.

“Shin’s body shows more scars from torture than any camp survivor I know who has come to South Korea, and I have met almost all of them,” said Ahn Myeong Chul, a former North Korean prison guard who for seven years worked for the National Security Agency, known as the Bowibu, the feared political police force that runs the country’s most notorious prisons, including Camp 14. Ahn is now executive director of NK Watch, a human rights group in Seoul, and knows Shin well.

“The scars prove to me that Shin was tortured at a Bowibu detention center,” said Ahn, who sees Shin’s scars as signature work of his previous employer.

Shin buried his memory of fingernail torture—and kept it from the world for nearly a decade—because he said it had been unbearable, physically and psychologically.

“I couldn’t handle it,” he said. “I tried to scrunch my fingers up so they couldn’t pull out more fingernails.”

Shin said this infuriated the guards, who forcibly straightened out the middle finger on his right hand and smashed the end of it with some kind of club. The blow effectively amputated the finger up to the first knuckle. Previously, Shin had said that guards cut off that part of his finger with a knife, as punishment for dropping a sewing machine in a camp uniform factory. But he now says he made up that story because he was ashamed of how he had been “broken” by torture.

In 2010, Shin admitted to me that when he first arrived in South Korea, he concealed how his mother and brother got caught—and were later executed—for planning an escape from prison camp. They were caught, he told me, because he betrayed their plans to a guard. An extended account of that betrayal appears in Escape from Camp 14.

In our new round of interviews, Shin changed the story again, saying his role in the executions was more shameful than he could bear to admit.

“I was jealous of my brother because my mother liked him more than me,” he said. “My mother never liked me much. She beat me much more than my brother. She never paid attention to my birthday.”

Shin said that in 1996, after he snitched to a guard about the escape plans of his mother and brother, he put his thumbprint on a police statement he knew to be false. It stated that he had seen his mother and brother commit a murder. Shin said the document, which a guard asked him to sign, was important evidence for the execution. Shin was fifteen at the time, according to a North Korean government listing of his birthdate, which says he was born on November 19, 1980. (Shin now says he is not sure what year he was born but that his father told him it was 1982.)

Shin has also acknowledged that there were some fictive elements in his former narrative. He did not live in a student dormitory in Camp 14 when he was a teenager; he lived with his father in Camp 18. During his second journey to the Chinese border, he was not “shocked” to see North Koreans shopping in street markets. He had seen them shop before, during his first flight to China.

He said he altered dates and locations for major events, such as the age at which he was tortured; he was twenty-one, not fourteen. He changed the whereabouts of the execution of his mother and brother. It occurred at an execution site beside the Taedong River in Camp 18, not on the other side of that river at an execution site in Camp 14.

When Shin began telling his story to South Korean intelligence, to human rights investigators, and to the world’s press, he said he had no idea that these details would later be considered important. He did not know what fiction or nonfiction was. He had never read a book. He said he only learned the concept of nonfiction when I told him that’s what I had to write.

Shin said he had much to be ashamed of and even more to hide when powerful people in South Korea started asking him questions. So he shaped his answers to serve his needs, not those of government interrogators, or human rights organizations, or journalists like me.

As I have explained, trauma experts see nothing unusual in this. What is unusual is that his story made him an international celebrity.

Unintentional corroboration

Some key elements of Shin’s revised story have been unintentionally corroborated by North Korea itself, in press releases, statements at the United Nations, and two propaganda videos released in the fall of 2014.

That is when the government in Pyongyang, in a furious push to derail criticism of its human rights record, zeroed in on Shin, attacking him repeatedly by name and describing him as “scum” and a “parasite.”

In the process, North Korea confirmed that Shin’s mother and brother were executed in 1996 for “premeditated murder with grave consequences” and said Shin played a role in their punishment. A press release from North Korea’s U.N. mission in New York said Shin did indeed escape twice to China. Between escapes, the release said, Shin failed to show “true regret” and made no effort to “redeem his crime.”

North Korea and witnesses it showcased in its videos also accused Shin of being a “criminal,” a thief who fled the country after raping a thirteen-year-old girl. He categorically denies any rape but acknowledges he did steal clothes and food while traveling across North Korea during his escapes to China. North Korea has not presented evidence that Shin was arrested or tried for rape but says he fled to China after committing his crime. North Korea’s videos have explained Shin’s scars as the result of various mining accidents and a childhood mishap that spilled “hot dog food” on his lower back when he was two.

In one government-released video, Shin was stunned to see his father, Shin Gyung Sub, whom he had thought was dead. The father insists in the video that neither he nor his son had ever lived in a “so-called political prison camp.” But the father himself also undermines that claim. He says that Shin was a young boy in the town of Pongchang, which at the time was inside the borders of a political prison.

North Korean records seem to support Shin’s contention that he was born in a part of Camp 14 that was incorporated into Camp 18 when he was six or seven. The shift in administrative borders occurred in 1984, according to records located by Curtis Melvin, a researcher for the U.S.-Korea Institute at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies.

Based on the limited information in these records, Melvin said Shin’s story about being born and living as a small child in Camp 14 is “plausible.” Researchers at two respected human rights groups in Seoul share this assessment.[1] But records do not explicitly delineate camp borders. Instead, they show that Shin’s home area was part of Kaechon County, where Camp 14 is located, until 1984. Then it came under the jurisdiction of Pukchang County, which administered Camp 18.

Ahn, the former prison guard, said it would have taken two or three years after the official change of county borders in 1984 before the political police in Camp 14 handed over control of Shin’s home area to the less restrictive regular police who ran Camp 18. Ahn believes that during that time Shin would likely have been living in conditions very much like those described in Escape from Camp 14.

“Shin probably did grow up until he was six or seven as a very restricted prisoner,” Ahn said. He and other human rights groups say more research is necessary to determine with certainty whether Shin was indeed born in Camp 14. Yet, by his father’s videotaped admission, Shin was a child inside Camp 18 and lived just 1.3 miles from the borders of Camp 14.

After North Korea attacked Shin by name in the late fall of 2014, the security authorities in South Korea began providing him with twenty-four-hour police protection. In the past, North Korea has sent assassins to Seoul to try to kill high-visibility defectors.

The story he first told in 2006

Before Shin arrived for the first time in South Korea in 2006, he said he spent several months in Shanghai, waiting inside the South Korean consulate for clearance to travel to Seoul. He learned from consulate staff that he would have to give an account of his life to South Korea’s National Intelligence Service.

When he heard about the coming interrogation, he was frightened and said he began to formulate a sanitized version of his life story. It omitted fingernail torture and his role in the execution of his mother and brother.

“It was a way of streamlining my story; it just happened,” he told me. “In China I never wrote down anything, just worked it out in my head.”

Having composed this script, Shin stuck to it during weeks of questioning by South Korean intelligence. Matthew E. McMahon, then an interrogator with U.S. Army Intelligence, also questioned Shin and remembers that he seemed severely traumatized. But McMahon also said that the story he heard from Shin was remarkably consistent with what he would say over and over again in future press interviews.

While the stories of many trauma victims tend to change over time, Shin’s did not. He kept it straight by writing it down as soon as he could. He did so in the Seoul offices of the Database Center for North Korean Human Rights, which gave him office space, a place to live, and two years of psychotherapy.

“It was Shin’s idea to write his book, and he did it by himself. We only corrected the spelling and grammar,” said Alice Sunyoung Choi, director of international communications for the Database Center, which published the Korean-language memoir in 2007, just a year after he arrived in South Korea.

After that, Shin often instructed curious reporters to “read my book.”

His one significant change in the script was with me in 2010, when we were winding up interviews for this book. He told me that he had not been truthful about the reasons for the executions of his mother and brother.

When Shin made this admission, I asked him what else he had been lying about. He claimed then that there was nothing else. But now he says he was on the brink of spilling his long-repressed secrets.

“I was beginning to tell you the truth, but I just stopped,” he said. “It was too painful. There were parts I could not stand recalling. At that point, I made up my mind not to tell anyone the truth. I would have covered it up forever if my father hadn’t appeared in the video.”

Video of Shin’s father

When the video was posted on YouTube in October of 2014, Shin struggled to suppress his alarm. For a while, he succeeded.

From my home in Seattle, I reached him and asked him to explain what was going on. Why was his father saying that he and Shin had never been in a political prison? Shin said his father was under pressure to lie (which does seems likely) and that he was worried about what North Korea would do to him next. To explain himself, Shin wrote (with my editing help) an op-ed for the Washington Post. In it, he asked North Korea to let him see his father, while insisting that he would not be silenced. Shin said basically the same thing to the New York Times.

The video, meanwhile, angered Camp 18 survivors in Seoul. They began to grumble and privately accused Shin of being a liar.

Among the survivors was Kim Hye Sook, who spent twenty-eight years in Camp 18 before being released and finding her way to South Korea in 2009. Like Shin, she has testified around the world and written a book about her life.

Kim, who is sixty-two, recognized Shin’s father in the video, as well as his uncle, who also appeared in it. She said she knew Shin’s mother, having attended years of political “reeducation” meetings with her in the camp. Kim also remembered watching the 1996 execution of Shin’s mother and brother. (She says both were shot; Shin says only his brother was shot and his mother was hanged.)

The North Korean video confirmed Kim’s long-held suspicion that Shin had grown up in Camp 18. When she and Shin had made joint appearances for human rights events, she felt Shin avoided talking to her about prison life. She found his behavior suspicious. After seeing the video, she was furious. She now says she cannot believe anything he says.

“He gave North Koreans an excuse to say we are all liars and to deny its human rights abuses,” she told me. “Now, when I come forward with my story, somebody might be suspicious of me. I have to watch my back.”

A few days after the video of his father appeared, Shin went to see Ahn, the former prison guard and human rights activist whom he had come to regard as his “big brother.” Shin admitted he had lived in Camp 18 and conceded that other parts of his story were not accurate.

According to both men, Ahn advised Shin to wait awhile before going public. He said they should remain silent until after the UN Security Council considered a General Assembly resolution that referred North Korea to the International Criminal Court on charges of crimes against humanity. The Security Council debate took place in December 2014, with no action taken.

How Shin now says he escaped

As Shin now tells it, he escaped Camp 18 twice, once in the spring of 1999 and again in the late winter of 2000, crawling under the same section of electric fence both times. He barely felt any voltage in the fence the first time and none the second. By the late 1990s, parts of Camp 18 were much less restrictive than in previous decades, and some areas were poorly guarded, according to Kim Hye Sook and the testimony of others who lived in the camp.

The first escape, Shin said, was suggested by his father, who gave his eighteen-year-old son a letter and told him to go to the home of Shin’s aunt in Mundok County, a journey of about thirty miles. According to Shin, it took him two weeks to find the place, and when he arrived, camp guards were waiting for him. They brought him back to Camp 18 and sent him to a detention center near the Taedong River, where he did forced labor, including work at a nearby hydroelectric dam (as described in Escape from Camp 14). After about a year and a half, he said, he escaped again.

This time he made it to China (as North Korea acknowledges) and worked there cutting trees for four months before local police caught him. North Korea says Shin was repatriated from China and “transferred back to our law enforcement agencies” in 2002. Shin said the date was 2001.

Guards again took him back to Camp 18 and allowed him to see his father one last time. A description of this final and sullen leave-taking occurs in Escape from Camp 14, although the location and timeframe differs from the one Shin now describes. After seeing his father, Shin said, he was driven across the Taedong River to a detention and torture facility inside Camp 14.

Shin located the building for me on Google Earth. He had located the same building for a 2012 interview with 60 Minutes. It appears to be surrounded by a high wall and looks like a National Security Agency facility, according to Ahn, the former guard who said he has seen similar buildings at four political prison camps.

“The place in Camp 14 that Shin has pinned as the location of his torture is clearly a detention center,” Ahn said. “This is the most horrible place in the camp. There is usually a basement room used for torture. When a camp is closed, these are the first places guards blow up to remove evidence.”

After about a month of torture (Shin lost track of time), he spent six months in a detention center cell, where he said an elderly prisoner helped him recover. Shin said he was then released into the general camp population. For the next three years, he worked in a mine, on a farm, and then in a uniform factory. Much of this, he said, is as described in Escape from Camp 14.

Shin’s knowledge of the camp’s geography and the function of its many buildings has impressed several human rights investigators. “We can only tell you that we are certain that he had been in Camp 14 because of the things he knew about the operation of the camp and his knowledge of construction projects inside it,” said Alice Sunyoung Choi of the Database Center in Seoul. (His knowledge of Camp 18’s geography and its buildings also squares with that of longtime resident Kim Hye Sook.)

Shin maintains that his January 2005 escape from Camp 14 occurred as described in this book, noting that the extraordinary scars on his legs were caused by that camp’s high-voltage electric fence.

But some details of his escape differ from what he has said before: He was motivated to escape, he now says, because he had been informed that he was scheduled to be executed in February of that year. He also said he was not nearly as naive as he had earlier claimed to be about the world outside the camp’s fence.

There are no witnesses to confirm any of this, and some Camp 18 survivors, including Kim Hye Sook, have said Shin could not have escaped Camp 14 and made it all the way to China since no one else is known to have done it. One Camp 18 survivor (who has declined to grant interviews) has told human rights activists that the inmate Shin claims was his accomplice in escaping Camp 14 actually died elsewhere in a mine accident.

Ahn, too, has questions.

“I can understand that he might be able to get out of the camp because guards are not always alert,” he said. “But his escape would have created an alert. How could he pass the security points in North Korea? How come no one caught him in the train station?”

Shin said security forces did look for him in 2005, but he knew how to travel anonymously across North Korea because he had done it before, having used the same escape route in 2001. Until more evidence emerges, that is where his story stands, with Shin turning up in China in 2005.

The power of an individual story

Experts have known with certainty about the scale of suffering in the North Korean gulag since at least 2003, when eyewitness testimony was correlated with satellite pictures. Since then, as satellite imagery has been refined, there has been a flood of reports, white papers, and commission findings. Scores of camp survivors have given accounts of murder, rape, beatings, torture, slave labor, and starvation.

But for much of the past decade the general public, especially in the United States, barely noticed.

This is not an anomaly. The suffering a totalitarian state secretly inflicts on its own people has historically been difficult for nonexpert outsiders to comprehend or care about.

What can change public perception is a powerful story about one individual.

Consider Stalin’s gulag. The Western world focused its attention on labor camps in the former Soviet Union only after the publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, a short novel based on Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s eight years in the gulag.

Spare, quick to read, and emotionally explosive, the book became the single most searing indictment of the gulag, even though it appeared in 1962, nine years after Stalin died and the camps began to close.

Shin, of course, is no Solzhenitsyn. He is not a poet, a journalist, or a historian. Raised in a dysfunctional family in a secret prison, badly educated, and tortured, he is a flawed eyewitness to the savagery of the world’s last totalitarian state. As he has often said of himself, he is an “animal” slowly learning how to be a human being.

It is not his fault he became globally famous during that learning process. I am accountable for that, along with plenty of other journalists and human rights groups. It is our business to grab the attention of a mass audience and to focus it on horror in distant places. We know how to do it: tell a human story, shattering and short.

Shin’s life is such a story. It is not fiction. It is journalism and history built around one young man’s memory, as refracted through a collapsed scheme to hide from trauma, torture, and shame. It should now be read in the light of all that Shin is willing to acknowledge and correct. As such, it reveals the depravity that North Korea continues to deny.

—————–

[1]. The Citizens’ Alliance for North Korean Human Rights and the Data Base Center for North Korean Human Rights.

——————————————

Reviews of Escape

“Harden’s book, besides being a gripping story, unsparingly told, carries a freight of intelligence about this black hole of a country.”—Bill Keller, New York Times

“The central character in Blaine Harden’s extraordinary new book Escape from Camp 14 reveals more in 200 pages about human darkness in the ghastliest corner of the world’s cruelest dictatorship than a thousand textbooks ever could…Escape from Camp 14, the story of Shin’s awakening, escape and new beginning, is a riveting, remarkable book that should be required reading in every high-school or college-civics class. Like “The Diary of Anne Frank” or Dith Pran’s account of his flight from Pol Pot’s genocide in Cambodia, it’s impossible to read this excruciatingly personal account of systemic monstrosities without fearing you might just swallow your own heart…Harden’s wisdom as a writer shines on every page.”— The Seattle Times

“Reads like a pulse-pounding thriller. This book will make you cheer. It will also make you cry.”– The Today Show

“Escape from Camp 14″ sits alongside a literature of holocausts … like “The Diary of Anne Frank” and “The Gulag Archipelago” that damn their political and institutional spaces to eternal opprobrium and hostility — Sino-NK website

Winner of the 2012 Grand Prix de la Biographie Politique. Judges of the French literary prize recognized a book that they said “plunges the reader into a world of extreme and unimaginable inhumanity.” Finalist for Dayton Literary Peace Prize. Inspired a segment about Shin on 60 Minutes.

“In a very brief time, Escape from Camp 14 has become a famous book… It is well-written and easy to read even if its subject is horrific. Since it began life in the form of a newspaper article, it has been serialized on BBC radio and extracted around the world in a variety of other newspapers. It tells the story of a man now called Shin Dong-hyuk, who lives in Seoul after having spent some time in the United States. But he was formerly Shin In Geum, born in one of the toughest North Korean labour camps where there was no faith, hope or charity, just sheer mind-boggling brutality.” — Asia Literary Review

“A remarkable new book.” — The Economist

“A must-read… Anyone puzzled by the North Korean conundrum should read this book. By telling the story of one very unusual young man, Escape opens a unique window onto life in the DPRK.” — Los Angeles Review of Books

“Blaine Harden of the Washington Post is an experienced reporter of other hellholes, such as the Congo, Serbia, and Ethiopia. These, he makes clear, are success stories compared to North Korea…Harden deserves a lot more than ; ‘wow’ for this terrifying, grim and, at the very end, slightly hopeful story of a damaged man still alive only by chance, whose life, even in freedom, has been dreadful.”—Literary Review (London)

“Harden’s book is a necessary document against indifference,” — Die Welt

“A remarkable story, [Escape from Camp 14] is a searing account of one man’s incarceration and personal awakening in North Korea’s highest-security prison.”— The Wall Street Journal

“In this extraordinary biography, which reads like an adventure novel where dreams mingle with nightmares, Harden fills in precise details on North Korea and its terrible regime.” — L’Express

“As U.S. policymakers wonder what changes may arise after the recent death of North Korean leader Kim Jong Il, this gripping book should raise awareness of the brutality that underscores this strange land. Without interrupting the narrative, Harden skillfully weaves in details of North Korea’s history, politics and society, providing context for Shin’s plight.” — Associated Press

“As an action story, the tale of Shin’s breakout and flight is pure The Great Escape, full of feats of desperate bravery and miraculous good luck. As a human story it is gut wrenching; if what he was made to endure, especially that he was forced to view his own family merely as competitors for food, was written in a movie script, you would think the writer was overreaching. But perhaps most important is the light the book shines on an under-discussed issue, an issue on which the West may one day be called into account for its inactivity.”— The Daily Beast

“A riveting new biography…If you want a singular perspective on what goes on inside the rogue regime, then you must read [this] story. It’s a harrowing tale of endurance and courage, at times grim but ultimately life-affirming.”— CNN

“In Escape from Camp 14, Harden chronicles Shin’s amazing journey, from his very first memory–a public execution he witnessed as a 4-year-old–to his work with human rights advocacy groups in South Korea and the United States…By retelling Shin’s against-all-odds exodus, Harden casts a harsh light on a moral embarrassment that has existed 12 times longer than the Nazi concentration camps. Readers won’t be able to forget Shin’s boyish, emancipated smile–the new face of freedom trumping repression.”— Minneapolis Star-Tribune

“Harden expertly interleaves thoughtful reports on the larger North Korean context into the more personal part of the narrative. Precise and lucid, he fills us in on this totalitarian state’s workings, its international relations and its devastating famines…This book packs a huge wallop in its short 200 pages. The author sticks to the facts and avoids an emotionally exploitative tone — but those facts are more than enough to rend at our hearts, to make us want to seek out more information and to ask if there isn’t more than can be done to bring about change.”— The Oregonian

“Many good books will be published this year. This one is absolutely unique…Shin Dong-Hyuk is the only person born in a North Korean political camp to escape and defect. He told his story at length to veteran foreign correspondent Blaine Harden, who wrote this extraordinary book…I don’t say that there’s an answer to the issues raised by this book. But there is a question. And the question is: “High school students in America debate why President Franklin D. Roosevelt didn’t bomb the rail lines to Hitler’s caps. Their children may ask, a generation from now, why the West stared at far clearer satellite images of Kim Jong Il’s camps and did nothing.” This is tough reading. Read it.”—Don Graham, CEO of The Washington Post, in a review at Amazon.com

“This book must be read, must be studied page by shuddering page, and from thence, our nation must begin to demand accountability from Pyongyang not only for its capabilities to harm the world, but also for its willingness to harm its own citizens.”— Partisans

“[A] chilling [and] remarkable story of deliverance from a hidden land.”—Kirkus Reviews

“Harden tells a gripping story. Readers learn of Shin’s gradual discovery of the world at large, nonadversarial human relationships, literature, and hope—and the struggles ahead. A book that all adults should read.”— Library Journal (starred review)

“With a protagonist born into a life of backbreaking labor, cutthroat rivalries, and a nearly complete absence of human affection, Harden’s book reads like a dystopian thriller. But this isn’t fiction-it’s the biography of Shin Dong-hyuk.”—Publishers Weekly

“This is a story unlike any other… More so than any other book on North Korea, including my own, Escape from Camp 14 exposes the cruelty that is the underpinning of Kim Jong Il’s regime. Blaine Harden, a veteran foreign correspondent from The Washington Post, tells this story masterfully…The integrity of this book shines through on every page.”—Barbara Demick, author of Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea

“Through the extraordinary arc of Shin’s life, Harden illuminates the North Korea that exists beyond the headlines and creates a moving testament to one man’s struggle to retrieve his own lost humanity.”—Marcus Noland, co-author of Witness to Transformation: Refugee Insights into North Korea

“If you have a soul, you will be changed forever by Blaine Harden’s Escape from Camp 14…Harden masterfully allows us to know Shin, not as a giant but as a man, struggling to understand what was done to him and what he was forced to do to survive. By doing so, Escape from Camp 14 stands as a searing indictment of a depraved regime and a tribute to all those who cling to their humanity in the face of evil.”—Mitchell Zuckoff, New York Times bestselling author of Lost in Shangri-La

Online Focus, a major German weekly, examines young dictator Kim Jong Un, the old torturing ways of North Korea and Escape from Camp 14.

“Mr. Shin’s story, at times painful to read, recounts his physical and psychological journey from a lifetime of imprisonment in a closed and unfeeling prison society to the joys and challenges of life in a free society where he can live like a human being.”—Kongdan Oh, co-author of The Hidden People of North Korea: Everyday Life in the Hermit Kingdom

N Korea has itself said Shin Dong-hyuk escaped the country twice

Shin told me last week that he had twice fled North Korea for China. He made this new claim during an interview in which he changed some key elements of the story of his life in the North Korean gulag. He said that in 2001, when he was 19, he escaped political prison Camp 18 and fled north to China. After four months, he said, Chinese police caught him and sent him back to North Korea. Then he said he was taken by guards back to the gulag, first to Camp 18 and then to the more brutal Camp 14.

Last October 8, a press release from the North Korean mission at the UN in New York stated that Shin had indeed fled to China twice. It said that in 2002 Shin “was arrested by Chinese border guards for illegal border crossing. Thereafter, he was transferred back to our law enforcement agencies, but instead of showing true regret and trying to redeem his crime, he again made an illegal border crossing and ran over to the South.” North Korea did not say Shin escaped from political labor camps; it denies that they exist.

North Korea, however, did unintentionally disclose that Shin did live as a child in a political prison camp (Camp 18), according to Curtis Melvin, who writes the respected NK Economy Watch blog.

There are many details in Shin’s new story that have not been confirmed. But it seems fair to conclude that evidence exists to corroborate some significant aspects. The sources are North Korean propaganda videos and statements that denounce Shin as “scum” and a “parasite.”

Shin changes key parts of his story

Here is a statement that I have released to the press:

On Friday, January 16, I learned that Shin Dong-hyuk, the North Korean prison camp survivor who is the subject of Escape from Camp 14, had told friends an account of his life that differed substantially from the book.

I contacted him by phone on Friday and talked to him at length, pressing him to detail the changes and explain why he had misled me. I then passed on this information to the Washington Post, for which I originally wrote a story about Shin in 2008.

[The Post reported its own story, which was published online Saturday, Jan. 17. The New York Times posted its story on Sunday, Jan. 18.]

Shin, 32, who lives in Seoul and whose testimony was a major factor in United Nations condemnation of North Korea for human rights violations, now says that he twice escaped to China from two different prison camps in North Korea. After his first crossing into China in 2001, he says he was caught after four months by local police and sent back to North Korea.

Shin now says that he was tortured in Camp 14 in 2002, when he was 20 years old, as punishment for his defection to China. In the book, he gave an account of being tortured in the camp when he was 13 years old. Shin has been telling that version for nearly nine years, since he first arrived in South Korea from China in 2006 and was debriefed by South Korean and American intelligence officials.

“When I agreed to share my experience for the book, I found it was too painful to think about some of the things that happened,” he said. “So I made a compromise in my mind. I altered some details that I thought wouldn’t matter. I didn’t want to tell exactly what happened in order not to relive these painful moments all over again.”

Escape from Camp 14 was first published by Viking in 2012 and published in paperback by Penguin in 2013. It has been published in 27 languages.

It appears that much of Shin’s revised account is consistent with the story told in the book and with his testimony before a U.N. Commission of Inquiry on human rights abuses in North Korea: He says he was tortured in Camp 14, a sprawling prison in the mountains of North Korea. He also says he escaped the prison in 2005 by climbing over the body of a fellow inmate who was electrocuted on the fence that surrounds the camp.

But he has significantly revised details of his early life and substantially changed the dates and places of major events. He says that he was born in Camp 14, but when he was about six years old, he and his mother and brother were transferred to another nearby prison camp, Camp 18, located just across the Taedong River.

It was in Camp 18, Shin said, that he betrayed his mother and brother, after overhearing their plans to escape. It was also in this camp, he said, that he witnessed the execution of his mother and brother. (In the book, these events were described by Shin as occurring in Camp 14.)

For the first time, Shin now says he twice escaped from Camp 18 when he was a teenager, first in 1999 and then in 2001. After the first escape, he was caught within a couple of days. Following his second escape, he managed to travel to China. But police arrested him there, he said, and sent him back to North Korea. Guards returned him first to Camp 18 and then, for punishment and torture, to Camp 14, Shin said in the interview.

In Escape from Camp 14, Shin describes how guards tortured him by fire in that camp when he was 13 years old, when they suspected him of plotting to escape with his family. His lower back is still scarred from severe burns.

But in the phone interview, Shin said that he was actually tortured much later, when he was 20. It happened, he said, after his return from China. In Camp 14 in 2002, he said, guards confined him in an underground prison for six months, where he was repeatedly burned and tortured.

It was then, he said, that part of one of his finger was mangled, as guards pulled out his fingernails. In Escape from Camp 14, Shin said an angry guard cut off the finger because Shin dropped a valuable sewing machine.

Asked why he had altered such details, when they in no way changed the horror of his story, Shin said he thought the dates, places and circumstances were not all that significant.

“I didn’t realize that changing these details would be important,” he said. “I feel very bad that I wasn’t able to come forward with the full truth at the beginning.”

In light of my conversation with Shin, I am working with my publisher to gather more information and amend the book.

Last fall, the North Korean government released a propaganda video showing Shin’s father. In the video, his father says that Shin never lived in a political prison camp.

Shin has said that the North Korean government was forcing his father to lie.

Now, Shin said in the interview, he realizes that his altered story puts his credibility at question.

“I am asking for forgiveness,” he said.

Escape from Camp 14 was part of World Book Night, when 250,000 books were given away in April in the UK.

Escape from Camp 14 was part of World Book Night, when 250,000 books were given away in April in the UK.

The aim is to put books in the hands of the 35 percent of the British population that normally doesn’t read for pleasure.

In Washington Post op-ed, Shin Dong-hyuk writes: North Korea will not silence me.

North Korea stages huge demo against UN vote that refers its human rights atrocities to International Criminal Court.

Pyongyang says vote was “an undisguised declaration of a war to disgrace the genuine human rights of the DPRK and infringe upon its sovereignty.” Leader Kim Jong Un describes Americans as “cannibals,” reports NYT.

Editorials in the New York Times and the Washington Post say N. Korea’s human rights abuses are abhorrent and warrant action by the UN Security Council.

The editorial pages of the Times and the Post have cited the influence of Shin Dong-hyuk and Escape from Camp 14 in raising world awareness.

Tantrum Time in Pyongyang:

A day after 111 nations voted to prosecute North Korea for crimes against humanity, its government called the vote a “grave political provocation” and threatened to blow up a 4th nuclear device.

UN refers North Korea’s human rights atrocities to International Criminal Court

During vote at UN headquarters, a N. Korean official tried — and failed — to get Shin Dong-hyuk thrown out of the proceedings.

After the vote, Shin Dong-hyuk with UN Ambassador Samantha Power

Frantic to stop UN vote that could lead to trial of Kim Jong Un, N. Korea smears Shin Dong-hyuk, the New York Times reports.

The Times says Shin’s “detailed disclosures about killings, torture, starvation and other deprivations in North Korea’s penal system, including the execution of his mother while he was forced to watch, are … an important component of a devastating report on North Korea’s human rights record.”

Shin Dong-hyuk receives an award for courage from Human Rights Watch

Shin Dong-hyuk receives an award for courage from Human Rights Watch

At the Beverly Hilton Hotel in LA, he said that when he crawled through the electric fence to escape from Camp 14, he never thought he would come to a place like America.

North Korea, as part of its campaign to block a trial of its leader for crimes against humanity, has released character-assassination videos about Shin Dong-hyuk.

Details and video links in the Washington Post and Reuters. Shin, the hero of Escape from Camp 14, was “Witness No. 1” at the UN’s Commission of Inquiry on human rights abuses in North Korea. The UN General Assembly and the Security Council are expected to vote soon on referring the Commission’s findings to the International Criminal Court. Those findings say that North Korean leader Kim Jong Un is responsible under international law for atrocities committed in the country’s political labor camps.

In the videos, Shin’s father says his son’s testimony is false and that he and his son “never lived in a so-called political prison camp.” Other witnesses in the video accuse Shin of everything from laziness, to rape, to stealing someone’s underpants. Until he saw the videos this week, Shin had long feared that his father had been killed in Camp 14. Shin last saw him on January 1, 2005, the day before Shin escaped the labor camp. After viewing the video, Shin now believes his father is alive. He also says his father is being “held hostage” by North Korea, which has coerced him into denouncing his son.

North Korea has a long history of using videos to attack defectors. In the Washington Post, Joanna Hosaniak of the Citizens’ Alliance for North Korean Human Rights, a Seoul-based nongovernmental organization, describes North Korea’s campaign to derail a trial as “a total hoax.” She added: “They’re trying to wage this war because they are so afraid that they will be referred to the International Criminal Court.

Momentum grew to try North Korea before the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity, the New York Times reports.

North Korea diplomats at U.N. have been forced to respond.

Secretary of State John Kerry, with Shin Dong-hyuk in NYC, tells North Korea to shut down the “evil system” of political labor camps. Complete text and video.

Secretary of State John Kerry, with Shin Dong-hyuk in NYC, tells North Korea to shut down the “evil system” of political labor camps. Complete text and video.

Spanish edition of Escape from Camp 14. In November from Kailas.

Spanish edition of Escape from Camp 14. In November from Kailas.

Human Rights Watch gives Shin Dong-hyuk an award for valor, honoring him as “the world’s leading advocate for closing North Korea’s camps.”

Human Rights Watch gives Shin Dong-hyuk an award for valor, honoring him as “the world’s leading advocate for closing North Korea’s camps.”

On the Today Show, Escape from Camp 14 recommended as great summer read: “…a pulse-pounding thriller. This book will make you cheer. It will also make you cry.

Tourist biz booms in North Korea (earning hard currency for Kim family), even as regime detains tourists, reports Reuters.

An argument for the long-term good that would come from the collapse of North Korea.

My review in Washington Post of Dear Leader, a new book that looks inside the lives of the elite in Pyongyang and shows how China helps N. Korea catch high-value defectors.

My review in Washington Post of Dear Leader, a new book that looks inside the lives of the elite in Pyongyang and shows how China helps N. Korea catch high-value defectors.

N. Korea grabs another US tourist. Maybe it is wise not to visit world’s worst human rights abuser and its smiling leader.

The Guardian puts Escape from Camp 14 on its list of best North Korea books

Shin Dong-hyuk receives honorary doctorate

And speaks to a standing-room-only audience at a U.S. Air Force Base in South Korea.

More than 684,000 people have watched this brilliant John Green vlog about Shin Dong-hyuk and Escape from Camp 14.

UN Security Council moved toward holding NKorea accountable for crimes against humanity that exceed all other nations in “duration, intensity & horror.” Thirteen of 15 member nations attended meeting. Nine supported sending case to International Criminal Court. China & Russia did not show.

Shin Dong-hyuk to testify at an informal meeting of the UN Security Council, marking first time a NKorean defector addresses the Security Council.

Congratulations to Shin Dong-hyuk. He will receive an honorary doctorate from Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The hero of Escape from Camp 14 is being recognized as “the foremost activist for human rights in North Korea.”

Quick way to see how world shifted from being indifferent to N. Korea’s crimes to demanding justice in international criminal court. Shin Dong-hyuk & Escape from Camp 14 played key roles.

Modest proposal: Deny N. Korea the global status it craves. De-recognize the country because of its crimes against humanity. Botswana did it. See excellent NK blog by Haggard and Noland.

The Economist has chilling drawings of N. Korea’s gulag, plus analysis of China’s pickle as patron of a state charged with crimes against humanity.

Washington Post editorial: This week’s UN report on N. Korea’s crimes against humanity is “a text that compares in significance to The Gulag Archipelago.”

On MSNBC, I discuss UN report on North Korea’s crimes against humanity & China’s likely veto of a trial.

60 Minutes replays piece on Shin Dong-hyuk, “Witness No. 1” at UN’s inquiry into NKorea’s crimes against humanity.

In case of war, guards in North Korea’s gulag have orders to kill everyone & destroy evidence, UN reports says.

North Korea’s young leader, Kim Jong Un, could face trial for crimes against humanity, U.N. commission says.

UN Commission of Inquiry finds that N. Korea has committed crimes against humanity, AP reports.

In its cover story on the “Holocaust in North Korea,” the Jewish Journal features Shin Dong-hyuk and Escape from Camp 14. Magazine’s publisher says this is “one of the most important pieces the Jewish Journal has published in our 28-year history.”

BBC World TV piece on the torment of Shin Dong-hyuk in Camp 14.

Rodman on CNN replies to criticism of his basketball game in North Korea: “I don’t give a rat’s ass what the hell you think.” The other former NBA players look uncomfortable.

Good AP piece on the (mostly) troubled and (often) bankrupt former NBA players who followed Rodman to NKorea.

Dennis Rodman returns to NKorea with NBA pals to honor Kim Jong Un’s birthday.

In the Washington Post, Shin Dong-hyuk tells Dennis Rodman how to behave in North Korea.

Everything you need to know about the curious purge of Uncle Jang & rise of NKorea’s new “Great Leader” by Haggard/Noland in superb blog posting.

With publication in Spanish (Kailas), Italian (Edizioni Codice) and Latvian (Zvaigzne ABC), Escape will soon be translated into 27 languages.

Escape from Camp 14 hits top ten list (#3) for book-club reads this winter, as chosen by independent book stores.

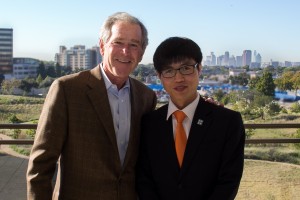

George W. Bush talked with Shin Dong-hyuk at Bush Presidential Center in Dallas on 23 October. Bush asked Shin about his life in and escape from Camp 14.

Historian Adam Cathcart’s full interview with me about how Escape from Camp 14 is becoming an icon of survival literature.

“I believe human rights mean eating what one wants to eat and saying what one wants,” Shin Dong-hyuk, aka “Witness No. 1,” said to the UN’s Inquiry into human rights atrocities in NKorea. See story from Japan’s Asahi Shimbun.

The Telegraph in London reviews Escape from Camp 14, calls it “riveting.”

Transcripts and video of UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in NKorea. Includes testimony of Shin.

UN investigation of human rights abuses in NKorea finds “shocking” evidence of widespread atrocities requiring an international response.

Escape in 27 languages

Available now in the United States (Viking), Britain (Mantle), France (Belfond), the Netherlands (Balans), Brazil (Intrinseca), Germany (Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt), Japan (Hakusuisha), Finland (Ajatus Kirjat), Denmark (Kristeligt Dagblads Forlag), Sweden (Norstedts), Norway (Cappelen Damm), South Korea (Asan Institute for Policy Studies), Poland (Weltbild), Russia (Exmo), Slovakia (Vydavatelstvo Tatran), Slovenia (Ucila International Zalozba), Croatia (Benedikta), Serbia (Grafički atelje Dereta), Czech Republic (Euromedia Group), Hungary (HVG), Israel (Ma’ariv), Lithuania (Eugrimas), Romania (Corint), Sanskrit (Sanskrit Book), and in non-mainland Chinese-speaking countries (iG Publishing). To be published soon in Spain (Kailas), Italy (Edizioni Codice) and Latvian (Zvaigzne ABC).

New report on changes in North Korea’s Gulag by David Hawk and the Committee on Human Rights in North Korea.

Washington Post editorial on North Korea’s gulag says future historians will wonder how world could know so much about labor camp horrors and still do nothing.

In this wonderful story by David Pilling, the hero of Escape from Camp 14 has lunch with the Financial Times.

Escape from Camp 14 named a nonfiction finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize.

Wall Street Journal reports N. Korea is trying to halt defections and silence rising voices of labor camp survivors like Shin Dong-hyuk.

New York Times reports on Shin Dong-hyuk’s testimony before U.N. Commission of Inquiry into human rights abuses in N. Korea: “…they were keeping us as beasts of labor, to get the most out of us before we die.”

Escape from Camp 14 “is one of a short but growing list of essential touchstones in a tragic new cultural genre,” writes Adam Cathcart, editor-in-chief of Sino-NK. His interview with me in Yonsei Journal of International Studies, Spring, 2013

Speaking in English, Shin Dong-hyuk accepts award for “stirring the conscience of mankind.”

Yes, Americans, you can travel for fun to N. Korea. You could also travel for fun to prewar Nazi Germany. Daily Beast’s Lloyd Grove explains.

Shin Dong-hyuk wins UN Watch moral courage award .

Shin testifies about life in Camp 14 at European Union hearing.

Escape becomes part of “common core” at schools in Washington D.C., helping teens learn to read, writes Education Week.

CSMonitor reports Escape from Camp 14 has made Shin Dong-hyuk world’s “best-known advocate for exposing” NKorea’s gulag.

Shin Dong-hyuk wins 2013 Moral Courage Award from UN Watch, a Geneva-based human rights group.

On May 19, 60 Minutes updated its story on Shin Dong-hyuk & Escape from Camp 14. Correspondent is Anderson Cooper.

CNN says Shin Dong-hyuk and Escape from Camp 14 have changed global discussion on N. Korea.

“Shin’s story is being absorbed into the American experience…” reports Sino-NK, a website that covers NKorea.

Korean-language edition of Escape: Shin Dong-hyuk & I will be in Seoul May 2 for launch at ASAN Institute for Policy Studies.

If you want to attend, send RSVP to Ross Tokola at rosstokola@asaninst.org. For directions, check ASAN’s website (www.asaninst.org). Event starts at 10 a.m. and includes lunch.

UN votes to investigate human rights abuse in N. Korea gulag. Shin Dong-hyuk’s story about life inside Camp 14 put pressure on U.S. and other nations to support long-overdue inquiry.

Escape from Camp 14 “is the most compelling and influential memoir yet written about the camps,” writes Carl Gershman, president of the National Endowment for Democracy in a review. Escape is out in updated paperback edition March 26.

In Geneva, UN human rights expert testifies that situation has worsened in N. Korea, as young dictator Kim Jong Un attempts “what could be known as perfection of control of the whole country.”

Obama’s representative for N Korea singled out “courageous and charismatic” Shin Dong-hyuk and “excellent book” Escape from Camp 14 in testimony before Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.

Referring to Shin’s horrifying experiences in Camp 14, Special Representative Glyn Davies told the Senate committee: “The world is increasingly taking note of the grave, widespread, and systematic human rights violations in the DPRK and demanding action.” Davies said United States will support creation of a UN commission to investigate N. Korea’s abuses against its own people.

Amnesty reports satellite images show N. Korea has built a huge perimeter around Camp 14, sharply restricting civilian movement. Could Shin Dong-hyuk’s account of what goes on inside Camp 14 be causing jitters in Pyongyang?

Before Dennis Rodman revisits his “friend for life” Kim Jong Un, Sports Illustrated’s Peter King and the Boston Herald editorial page advise him to read Escape from Camp 14.

United States to support U.N. inquiry into possible crimes against humanity in N. Korea.

N. Korea’s triple crown: more powerful nukes, longer range missiles and expanded labor camps.

UN’s Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in N. Korea calls for international inquiry into possible crimes against humanity.

Thanks to Google Maps, N. Korea’s prison camps are easy targets for snark. My piece in Foreign Policy.

At the New Yorker, Evan Osnos recommends Escape from Camp 14 as “remarkable writing” that helps explain N. Korea.

Greatness of N. Korea’s young dictator is shown to inquiring minds in outer space. See Joshua Stanton’s blog, One Free Korea

As U.N. moves toward investigating human rights abuses in North Korea…

Young dictator Kim Jong Un suddenly gets huffy, shaking his nukes and missiles at the United States. This “don’t mess with me, I’m armed and crazy” strategy has worked for decades, as a cowed international community ignores unpleasantness in the labor camps.

Japan announces it will support a UN inquiry into labor camps in North Korea.

Next to Camp 14, a new political labor camp in North Korea? Satellite analysis by Curtis Melvin at North Korean Economy Watch. Map analysis by Joshua Stanton.

Demanding an international inquiry into human rights abuses in North Korea, UN Human Rights chief cites case of Shin Dong-hyuk, the hero of Escape from Camp 14.

In response, North Korea denounced “fictions about concentration camps of political prisoners,” saying its recent missile launch has “sent a shiver down the spine of the U.S..”

Canadian national radio rebroadcasts in-depth program about Shin Dong-hyuk and Escape from Camp 14.

Financial Times picks Escape from Camp 14 as a best book of the year. South China Morning Post says it is a literary highlight of 2012.

With N. Korea’s Dear Leader dead for one year, what’s new with Kim the younger? Better rockets, tighter borders, same old repression. My piece in Washington Post.

Online Focus, a major German weekly, examines young dictator Kim Jong Un, the old torturing ways of North Korea and Escape from Camp 14.

60 Minutes on Shin Dong-hyuk and Escape from Camp 14. Transcript.

Online, 60 Minutes reports on Shin’s adoptive family in Ohio and his accounts of hardship in Camp 14.

Blaine’s TEDxRainier talk about Shin’s life inside and outside of Camp 14.

Escape wins the Grand Prix de la biographie politique, a French literary award. The book “plunges the reader into a world of extreme and unimaginable inhumanity,” judges said.

Escape wins the Grand Prix de la biographie politique, a French literary award. The book “plunges the reader into a world of extreme and unimaginable inhumanity,” judges said.

Best book lists:

Christian Science Monitor picks Escape as No. 5 on its list of year’s best nonfiction. A Slate staff choice. School Library Journal names Escape as a best adult book for teens. Goodreads Choice Awards ranks Escape as No. 5 in history/biography. Canada’s largest bookseller, Indigo, picks Escape as the 8th best book.

Remarkable video report on Escape from Camp 14 from Germany’s 3sat network. Review in Der Tagespiegel (Berlin) compares Escape to Solzhenitsyn’s “Gulag Archipelago.”

Escape from Camp 14 has found an audience in translation. A bestseller in Switzerland, Germany, France, it was No. 1 bestselling nonfiction title in Denmark and Finland.

Escape from Camp 14 is a “must-read,” says the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Reviewer John Delury: “anyone puzzled by the North Korean conundrum should read this book. By telling the story of one very unusual young man, Escape opens a unique window onto life in the DPRK.”

Japanese translation of Escape from Camp 14 published in September.

Escape from Camp 14 is being published in German-speaking Europe. Der Spiegel has an excerpt and a story.

Shin Dong-hyuk and I were in Northern Europe in Sept. to talk about Escape from Camp 14

In Denmark, we were greeted by an extraordinary review in Weekendavisen, the country’s leading weekly of politics and culture. The first paragraph: “Very few books have given this reviewer the urge to declare war on another country, but Blaine Harden’s story about Shin’s escape from North Korea is one of them… These political prison camps are a disgrace to our collective conscience.”

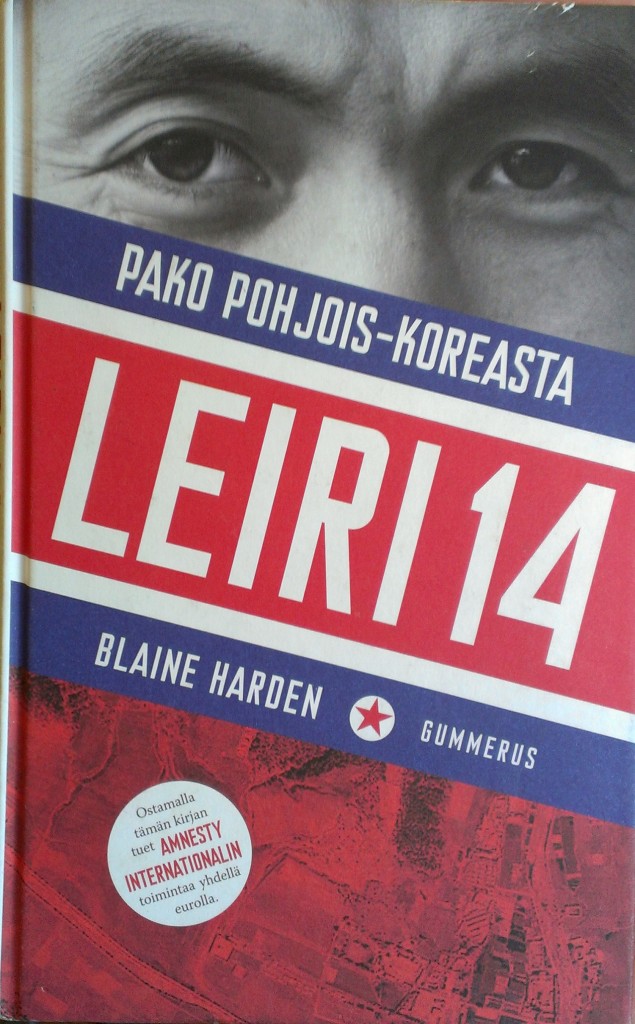

Escape was published in translation in Japan, Germany, Denmark, Finland and Norway. It will appear in Sweden in November. We were in Copenhagen, Helsinki and Oslo. The book cover here is the Finnish edition.

My interview with NPR’s On The Media:

NKorea’s effort to market a more huggable image, with a smiling young dictator and his smartly dressed young wife.

Review of Escape in Korea Review:

“In order to poke a hole in the world’s bubble of ignorance, Harden and Shin have produced a powerful and extraordinarily distressing story… The world may never forget the Holocaust, but they must first know about Camp 14.”

School Library Journal picks Escape from Camp 14 as one of the best books of 2012

A book for teens of all ages: YouTube review of Escape from Camp 14 on 60second Recap® PickoftheWeek

Asia Society interview: Blaine Harden on North Korea’s Gulags

Hindustan Times on Escape from Camp 14: “Harden gives us a book for which the adjective ‘shocking’ would be a shocking understatement.”

Canada’s National Post comments on Escape from Camp 14, calling it “dark and brutally unsentimental” and “extraordinary.”

Book Forum review of Escape from Camp 14: “A slim, searing, humble book — as close to perfect as these volumes of anguished testimony can be.”

Financial Times: “Escape from Camp 14 is a valuable read that casts a welcome spotlight on the most despicable regime on the planet.”

“IN A VERY BRIEF TIME, Escape from Camp 14 has become a famous book,” says the Asian Literary Review.

The story of Escape from Camp 14 “is so incredible, so rare and so in need of telling” that Canadian national radio gives it special attention.

Escape from Camp 14 is “a heart-crushing reminder that man’s inhumanity to man has no limit.” — Jeff Jacoby, Boston Globe

NY Times Op-ed: Bill Keller writes of Escape from Camp 14: “besides being a gripping story, unsparingly told, [it] carries a freight of intelligence” about North Korea.

Brian Lamb interviews Blaine about Escape from Camp 14 and life as a foreign correspondent on C-SPAN’s Q & A

Washington Post review praises Escape from Camp 14 as an “important portrait of man’s inhumanity to man” that is told in “spare, unadorned prose.”

Provocative review of Escape from Camp 14 in 3:AM Magazine, a literary magazine published in Paris.

Citing Escape from Camp 14, chief prosecutor of Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic co-writes online NYT/International Herald Tribune op-ed demanding U.N. investigation of N. Korean labor camps.

Superb special report on UK’s Channel 4 News (ITN) about Escape from Camp 14.

Reuters: Escape from Camp 14 “combines a thrilling and unique tale of escape with a harrowing memoir.”

Citing Escape from Camp 14, The Economist demands that the U.S stop hiding behind nuclear diplomacy, push harder on human rights.

New York Observer: The hero of Escape from Camp 14 steps out in Manhattan and does exceptionally well.

Citing Escape from Camp 14, Washingon Post calls for United Nations investigation of North Korean Gulag.

Fox News on North Korean gulag and Escape from Camp 14.

Excellent video interviews with book’s hero, Shin Dong-hyuk, and with me.

Reviews from the New York Times, the Guardian (London) and the Seattle Times:

NYT’s Janet Maslin calls Escape “a fast, brutal read.” Her review, though, incorrectly said that Shin Dong-hyuk tried to commit suicide in the camp by throwing himself down a mine shaft. The Times has published a correction. As hard as Shin’s life was in Camp 14, he never lost the will to live.

The Guardian’s Andrew Anthony says Escape is harrowing but important inquiry into “the gulag within the gulag.”

The Seattle Times’ Craig Welch says Escape is “a riveting, remarkable book that should be required reading in every high-school or college-civics class. Like “The Diary of Anne Frank” or Dith Pran’s account of his flight from Pol Pot’s genocide in Cambodia, it’s impossible to read this excruciatingly personal account of systemic monstrosities without fearing you might just swallow your own heart.”

Escape from Camp 14 climbs on New York Times bestseller list to No. 3 on ebooks and No. 12 on combined ebooks/hardbacks.

Wall Street Journal reviews Escape: “a searing account of one man’s incarceration and personal awakening.”

My op-ed in the Los Angeles Times about a real totalitarian state called North Korea and the pretend one in “The Hunger Games.”

On NPR’s Diane Rehm show, talking about Escape.

In the Christian Science Monitor, an amazing review of Escape.

“A book without parallel, “Escape from Camp 14” is a riveting nightmare that bears witness to the worst inhumanity, an unbearable tragedy magnified by the fact that the horror continues at this very moment without an end in sight.”

Amazon picks Escape from Camp 14 as a best book in April.

NPR’s All Things Considered: An interview about Escape. Blaine talks to Melissa Block

Escape “packs a huge wallop,” the (Portland) Oregonian says in a review.

Review concludes: “This book packs a huge wallop in its short 200 pages. The author sticks to the facts and avoids an emotionally exploitative tone — but those facts are more than enough to rend at our hearts, to make us want to seek out more information and to ask if there isn’t more than can be done to bring about change.”

CNN Reports: Escape from Camp 14 a true North Korea survival story

A Wall Street Journal live chat about Escape from Camp 14.

Associated Press review of Escape says the book is “gripping.”

Citing Escape, Washington Post editorial page editor Fred Hiatt writes that North Korea’s labor camps are plainly visible, “but people do not want to see them.”

The Atlantic excerpts Escape.

The Spectator (London) reviews Escape.

Canada’s National Post says Escape “makes The Hunger Games and its fellow dystopias read like Fantasy Island.”

The Wall Street Journal excerpt.

WSJ video report on the hero of Escape, Shin Dong-hyuk

WSJ Q & A with Shin

WSJ video interview with me

Escape is a BBC Book of the Week.

Starting Monday (March 26), it will be read on BBC Radio 4 in twice-daily installments through Friday. Readings will be available as podcasts for a week after broadcast. Radio 4 is the NPR of the UK.

The Guardian excerpt:

How one man escaped from a North Korean prison camp

The piece was a web sensation: read by 38,00o on Facebook, shared by 16,000. Tweeted by 3,000.

British book magazine, We Love This Book, on Escape

First major review. It’s a rave.

From the March issue of the Literary Review in London. By Jonathan Mirsky, a British journalist and East Asian expert.

Excerpts:

“Shin Dong-hyuk is the only person on earth born in one of North Korea’s hellhole concentration camps who has escaped and told his story. During his twenty-three years in Camp 14, a ghastly place even by North Korean standards, Shin knew absolutely nothing of the world beyond the electrified wire. From a new prisoner who had lived most of his life outside the camps, Shin learned that the world is round, that there is a city called Pyongyang and countries called South Korea and China, and that in those and many other countries people have computers, mobile phones and television, and use something called money.

“…what really fascinated Shin was that outside Camp 14 there were people who had enough to eat. ‘What he kept begging [for] were stories about food and eating, particularly when the main course was grilled meat,’ which Shin had eaten only when he had trapped a rat.

“Harden deserves a lot more than ‘wow’ for this terrifying, grim and, at the very end, slightly hopeful story of a damaged man still alive only by chance…

“Don’t imagine that this is a feel-good story about a man who has at last found happiness… [But] Shin has found a way of telling church and school groups in America what happened to him. Speaking to a congregation in Seattle, he recalled watching his teacher beat a six-year-old child to death in the classroom for hiding five grains of corn in her pocket. He told the shocked, weeping audience: “I didn’t think much about it. They educated us from birth so that we were not capable of normal human emotions. Now that I am out…I feel like I am becoming human.”

“Read it,” Don Graham, chairman and CEO of the Washington Post Co., writes about Escape on his Facebook page:

“Many good books will be published this year. This one is absolutely unique.

“Shin Dong-hyuk is the ONLY person born in a North Korean political camp to escape and defect. He told his story at length to veteran foreign correspondent Blaine Harden, who wrote this extraordinary book.

“Holocaust analogies are embarrassing, but what other analogy is there? This is the story of a modern death camp. Shin was confined there because two of his uncles had fled to the south during the Korean War. In 1951. Shin was born in 1982 and escaped in 2005. His first memory is of an execution. He watched his mother and brother executed (this is a complex, awful story). Prisoners are required to memorize ten rules; eight describe offenses for which prisoners “will be shot immediately.”

“Prisoners are barely fed, worked for 12-15 hour days and usually die of malnutrition-related illnesses before they turn 50. There are several such camps. The US State Department believes 200,000 people are confined in them.

“I don’t say that there’s an answer to the issues raised by this book. But there is a question. And the question is: ‘High school students in America debate why President Franklin D. Roosevelt didn’t bomb the rail lines to Hitler’s caps. Their children may ask, a generation from now, why the West stared at far clearer satellite images of Kim Jong Il’s camps and did nothing.’

“This is tough reading. Read it.”

Adam Johnson, author of an extraordinary new novel about North Korea, praises Escape on Facebook:

“The book is fleet and powerful–there’s no human story like it in the world. The tale of Shin Dong Hyuk was one that influenced aspects of my novel The Orphan Masters Son a great deal, and I’m indebted to Blaine for applying his great journalistic skills to bring this unique and powerful story fully to light.”

Wall Street Journal blog pre-welcomes Escape:

“Coming at the end of March is “Escape From Camp 14: One Man’s Remarkable Odyssey from North Korea to Freedom in the West,” the true story of Shin Dong-hyuk, who is the only person known to have been born in a North Korean gulag and escaped all the way to South Korea

“Written by Blaine Harden, former East Asia correspondent for the Washington Post, the book describes Mr. Shin’s awful, harrowing, tragic and ultimately affirming life,” blogs Evan Ramstad, the Journal’s bureau chief in Seoul.

Escape is part of a new “Korean wave” of books in English, Ramstad says. The others are “The Orphan Master’s Son,” a fabulous new novel about North Korea by Adam Johnson, whom I met in Seattle a few weeks back, and “Drifting House,” a collection of well-reviewed short stories about ordinary North and South Koreans by Krys Lee, a Korean-American writer who lives in Seoul. These two books have been published in recent weeks.

Ramstad writes that “both Ms. Lee and Mr. Johnson will soon be sharing store shelves with a book that may get even more attention because its subject matter is the darkest secret on the Korean peninsula – the concentration camps in North Korea.”

Foreign Policy picks Escape as one of the books that will matter in 2012

The first review is in: “Reads like a dystopian thriller.”

“With a protagonist born into a life of backbreaking labor, cutthroat rivalries, and a nearly complete absence of human affection, Harden’s book reads like a dystopian thriller. But this isn’t fiction—it’s the biography of Shin Dong-hyuk, the only known person born into one of North Korea’s secretive prison labor camps who has managed to escape and now lives in the U.S. Harden structures Shin’s horrific experience—which includes witnessing the execution of his brother and sister after their escape plan is discovered—around an examination of the role that political imprisonment and forced labor play in North Korea and the country’s fraught relationship with its economically prosperous neighbors South Korea and China While Shin eventually succeeds in escaping North Korea’s brutal dictatorship, adjusting to his new life proves to be extraordinarily difficult, and he wrestles with his complicity in the atrocities of his past—he informed on his mother and other brother, which led to their execution. “I was more faithful to the guards than to my family. We were each other’s spies,” he confesses. Harden wisely avoids depicting the West as a panacea for Shin’s trauma, instead leaving the reader to wonder whether Shin will ever be able to reconcile his past with the present. Harden notes both the difficulty of obtaining information about daily existence in North Korea and of fact-checking such information (including Shin’s own version of events), and the book’s brevity may leave readers wanting more from this brisk, brutal, sorrowful read.” Publisher’s Weekly, 10/10/2011

Starred review in Library Journal: “A gripping story… that all adults should read.”